“…but they were students, and to say student is to say Parisian; to study in Paris is to be born in Paris”

Victor Hugo, Les Misérables, page 120

“He loafed. To err is human, to loaf is Parisian”

Victor Hugo, Les Misérables, page 654

“But Gavroche, who was of the wagtail species and slipped quickly from one action to another, had picked up a stone. He had noticed a street lamp.

‘Well, well,’ he said, ‘you still have your lamps here. That’s not proper form, my friends. It’s disorderly. Sorry, this will have to go!’

And he threw the stone into the lamp, whose glass fell with such a clatter that some bourgeois, hidden behind their curtains in the opposite house, cried out, ‘There’s ‘Ninety-three all over again!’”

Victor Hugo, Les Misérables, pages 1157-58

There is a passage in the introduction to Les Misérables where Lee Fahnestock writes:

“Reading Les Misérables today, nobody would deny that Victor Hugo’s prodigious flow of words occasionally produces moments of excess, when we might wish he had shown more restraint”

(Introduction xii)

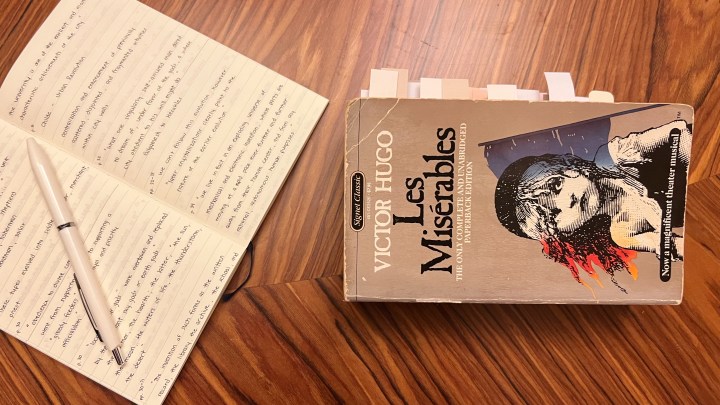

I disagree. I am happy that Victor Hugo did not show any restraint in his novel. Les Misérables is unlike any book I have ever read, and I doubt I will ever read another book like it in the future. It is a sprawling epic in every sense of the word. Hugo’s text is rich in detail and description and serves as a love letter to his beloved Paris. We see Paris through his eyes, “the Paris of his youth, that Paris he devoutly treasures in memory…as though it still existed.” (Hugo 446). Paris, its history; Paris, its buildings and streets and monuments; and Paris, the stories of its citizens. Everywhere in the novel you can see Hugo’s love for Paris. He names the streets as we walk alongside his characters. He tells us where streets intersect. He describes the buildings, the doors, windows, alleyways, the houses, colors, shapes, noises. He tells us what is here now and what was there before. His knowledge is encyclopedic but at no time does it feel dull or repressive. On the contrary, these passages represent some of the best parts of the novel. Victor Hugo was at heart a poet and like his contemporaries Pushkin and Lermontov, his prose is infused with the same magic that makes his poetry so memorable. To read Les Misérables is to read an epic in prose from a master of verse.

The unabridged English paperback version translated by Lee Fahnestock and Norman MacAfee finishes at 1463 pages. It is comprised of five volumes, each of which is named after one of the main characters, with the exception of Book IV, which is named after two streets in Paris where the main action of the book takes place. Book IV is titled “Saint-Denis and Idyll of the Rue Plumet”. Rue Plumet is the deserted street where Jean Valjean and Cosette take refuge in the secret house. It is here where Cosette falls in love with Marius “in that poor, wild garden” (Hugo 1004). Cosette, who “gave anyone who saw her a sensation of April and of dawn” (Hugo 1007), who was “a condensation of auroral light in womanly form” (Hugo 1007). Rue Saint-Denis is the street that leads to the action at the barricade. From this street in 1832, a pedestrian could turn and walk down the Rue de la Chanvrerie, a narrow street that Hugo described as an “elongated funnel” (Hugo 1083). It is here on the Rue de la Chanvrerie where the pedestrian would see the “famous barricade” (Hugo 1082) built by Marius and the Friends of the ABC during the June rebellion of 1832. The barricade is fictional, but the reader has difficulty telling what is real and what is not real. Hugo’s narrative is a masterclass of historical fiction. The barricades were real. The streets were real. The rebellion was real. General Lamarque, one of Napoleon’s marshals and whose death and subsequent funeral triggered the rebellion, was real. Part of the beauty of this book is that everything feels real. Like we are reading a firsthand account of what happened.

We are introduced to four of the main characters through the first three volumes: Fantine, Cosette, and Marius. Jean Valjean, the story’s protagonist, lends his name to Volume V. However, the first character we are introduced to is Monsieur Charles-François-Bienvenu Myriel, M. Myriel for short, who is seventy-five years old and is the Bishop of Digne. He was appointed Bishop of Digne by Napoleon in 1806. The year we are introduced to him is 1815.

“Noticing that the old man looked at him with a certain curiosity, Napoleon turned around and said brusquely, ‘Who is this good man looking at me?’

‘Sire,’ replied M. Myriel, ‘you are looking at a good man, and I at a great one. May we both be the better for it.’”

(Hugo 2)

M. Myriel serves as the moral guide for the story.

“What enlightened this man was the heart. His wisdom was formed from the light emanating there.”

(Hugo 56)

“There are men who work for the extraction of gold; he worked for the extraction of pity. The misery of the universe was his mine. Grief everywhere was only an occasion for good always. Love one another: He declared that to be complete; he desired nothing more, and it was his whole doctrine.”

(Hugo 57)

We are introduced to our protagonist, Jean Valjean, when he enters Digne in October 1815. He has “an indescribably sordid quality to his tattered appearance” (Hugo 59) and he carries with him a new knapsack and a large walking stick. To the citizens of Digne, he looks like a weary traveler who is in search of food and a room for the night. But something is wrong. We watch as he is cruelly turned away at an inn. Then, he is turned away at a tavern. Finally, he is turned away at the house of a peasant who threatens him with a gun. Growing increasingly more despondent, he is told by a kind woman from the church that he should knock on M. Myriel’s door. We find out that he is turned away from the inns because he carries the yellow passport of a convict. He was just released from prison after nineteen years, where he served five years for burglary and fourteen years for four attempted escapes. The bishop accepts him into his home. He politely asks him to stay for dinner, and he offers him a bed for the night. Jean Valjean is overwhelmed with gratitude. He is taken aback by the outward display of humanity he receives from the bishop.

“Everytime he said this word ‘monsieur’, with his gently solemn and heartily hospitable voice, the man’s face lit up. Monsieur to a convict is a glass of water to a man dying of thirst at sea. Ignominy thirsts for respect.”

(Hugo 76)

But for M. Myriel, this isn’t just a display of humanity. It is who he is. He is a beacon of light. A personification of good. He only lives for others, especially for those who have suffered like Jean Valjean. Jean Valjean is so confused by this that he confesses he does not know who he is anymore. He tells M. Myriel about the suffering he has endured over the last nineteen years.

“Yes,” answered the bishop, “you have left a place of suffering. But listen, there will be more joy in heaven over the tears of a repentant sinner than over the white robes of a hundred just men. If you are leaving that sad place with hatred and anger against men, you deserve compassion; if you leave it with goodwill, gentleness, and peace, you are better than any of us.”

(Hugo 77)

The bishop lives with his sister and a domestic servant. Before dinner, he asks his companions to set out the silver cutlery and two silver candlesticks that were customary when the bishop hosted anyone for dinner. During dinner, M. Myriel does not identify himself as the Bishop of Digne. Jean Valjean assumes he is a simple priest due to his meager possessions and his humble manner. He even questions M. Myriel before bed, expressing bewilderment that M. Myriel would let him sleep in a room near him. How does he know that Jean Valjean isn’t a murderer? M. Myriel casually dismisses his concern and blesses him before taking a walk in the garden.

Jean Valjean doesn’t have time to comprehend this action as he is so exhausted, he falls asleep immediately. He doesn’t even change out of his clothes. He wakes up in the middle of the night when everyone else in the house is still fast asleep. He immediately thinks of the silver pieces from dinner and the money he could earn from selling them. He silently sneaks into the bishop’s bedroom to look for them. He sees the bishop sleeping. He is frightened and spends a few agonizing moments contemplating his actions.

“The souls of the upright in sleep contemplate a mysterious heaven.

A reflection from this heaven shone upon the bishop.

But it was also a luminous transparency, for this heaven was within him; it was his conscience…

There was something close to divine in this man, something unconsciously noble.”

(Hugo 101)

Suddenly, without a sound, he unlocks the cabinet, puts the silver in his knapsack, and leaves the house. This is the second time he has committed theft. The first time he steals, he steals out of desperation. He is severely punished with a long prison sentence. The second time he steals, he steals for what? Revenge? Revenge against a system that has stolen his youth from him. Youth that he can attempt to buy back with the money from the silver. Or was it also desperation? Desperation at having suffered in prison only to be treated just as harshly when he becomes a free man. And then when he is at his absolute lowest point, when he is rejected by society, he is confronted by the divine goodness of M. Myriel, a man he can never be. It is like he resigns himself to his fate. He is a convict. He has no place in society so who cares if he steals or not?

Jean Valjean is quickly arrested and brought back to the bishop’s house. The gendarmes ask the bishop if the story that Jean Valjean told them is true. That the bishop gave him the silver cutlery. Jean Valjean bristles when he hears the gendarmes refer to M. Myriel as Monseigneur. He realizes that M. Myriel isn’t just a simple priest. The bishop replies in the affirmative and tells Jean Valjean that he forgot to take the silver candlesticks. He confidently goes to the mantelpiece and gives them to him. Jean Valjean is trembling and sitting there wordlessly “with an expression no human tongue could describe” (Hugo 105). The bishop gives him one final word in a low voice before he leaves:

“’Do not forget, ever, that you have promised me to use this silver to become an honest man.’

Jean Valjean, who had no recollection of any such promise, stood dumbfounded. The bishop had stressed these words as he spoke them. He continued, solemnly, ‘Jean Valjean, my brother, you no longer belong to evil, but to good. It is your soul I am buying for you. I withdraw it from dark thoughts and from the spirit of perdition, and I give it to God!’”

(Hugo 106)

M. Myriel gives him a second chance. Instead of a life sentence, he is given a new lease on life. Jean Valjean is left bewildered. We witness his inner toil as he struggles to comprehend the bishop’s compassion.

“…he must conquer or be conquered, and that the struggle, a gigantic and decisive struggle, had begun between his own wrongs and the goodness of this man”

(Hugo 111)

Jean Valjean undergoes a transformation. It is more than he can handle. He is broken open emotionally and he weeps for the first time in nineteen years.

“While he wept, the light grew brighter and brighter in his mind—an extraordinary light, a light at once entrancing and terrible”

(Hugo 113)

“How long did he weep? What did he do after weeping? Where did he go? Nobody ever knew. It was simply established that, that very night, the stage driver who at that hour rode the Grenoble route and arrived at Digne about three in the morning, on his way through the bishop’s street saw a man kneeling in prayer, on the pavement in the dark, before the door of Monseigneur Bienvenu”

(Hugo 113)

With this transformation, Jean Valjean takes on a heavy task. How does he become an honest man? Can he walk the same path as M. Myriel? It is his cross to bear and he must carry it with him for the rest of his life. The rest of the book attempts to answer that question for him. The reader is taken on an emotional rollercoaster ride in the search for the answer. But don’t let that deter you. Instead, let it inspire you. Hugo asks you to put your faith in him. To trust him to take you on this emotional journey. There will be high points and low points. But if you can stick with him until the very end, your faith will be rewarded.

Les Misérables is good because it portrays a realistic depiction of life. And it shows us what we can do when we love and sacrifice for each other. M. Myriel tells Jean Valjean: “Why would I have to know your name? Besides, before you told me, I knew it…your name is my brother” (Hugo 76). Love can’t be taken away. It pools up inside us from an eternal spring. We can draw from this spring for our entire lives. Now, does this novel advocate for a utopian society? No, because love is only one spring we can draw from. There will always be misery and greed in the world. Those springs seem infinite as well. What Hugo is telling us, reminding us, is that when times seem dark, when despair sets in, we just need to remember to love and sacrifice for each other. Hugo tells us the purpose of the book in the very beginning:

“So long as there shall exist, by reason of law and custom, a social condemnation which, in the midst of civilization, artificially creates a hell on earth, and complicates with human fatality a destiny that is divine; so long as the three problems of the century—the degradation of man by the exploitation of his labor, the ruin of woman by starvation, and atrophy of childhood by physical and spiritual night—are not solved; so long as, in certain regions, social asphyxia shall be possible, in other words, and from a still broader point of view, so long as ignorance and misery remain on this earth, there should be a need for books such as this”

(Hugo 1)

Hugo’s story is one of love and adoration, of despair and desperation, of promises kept. We see familial bonds stretched to their breaking points. We see the word family redefined altogether. We see youth cut down in its prime. We see generational conflict. We see redemption, hope, forgiveness, sacrifice. Sacrifice for our comrades. Sacrifice for those we love. Sacrifice for those we leave behind. Hugo presses us to reflect on this question: what does it mean to be human?

My favorite section of Les Misérables is the section on Waterloo. In fact, I was so excited to read this section that I planned to start it on a Friday night where I could sit at a café and do nothing but read and drink coffee. It is an unusual section because Hugo takes us out of the narrative and to the site of the famous battle.

The chapter starts with a flashback to May of 1861. Hugo finished his book in 1862. He tells the reader that he, a traveler and the author of the book, is walking from Nivelles from La Hulpe. He describes the scene like he would any other scene in his book. It is here again where we question whether this is real or fictional. We know now that he was indeed at Waterloo. It was here that he finished the novel. It is fitting because the Battle of Waterloo is where his story begins. I like this section for a couple of reasons. One is because I like Napoleonic history and this is the battle where Napoleon was defeated for the final time. Hugo tells us the story of the battle with such precision and intimate knowledge that it feels like he was present in both armies during the battle. We know that Hugo’s father served as an officer with Napoleon and Hugo was a teenager during the battle, so it isn’t presumptuous to think that he used firsthand accounts to help fill in his narrative. But he is quick to caution the reader that he doesn’t “claim to be giving the history of Waterloo” (Hugo 311).

“As for us, we leave the historians to their struggle; we are merely a distant witness, a passerby on the plain, a researcher bending over this ground steeped in human flesh, perhaps taking appearances for realities; we have no right in the name of science to cope with a mass of facts undoubtedly tainted with mirage; we have neither the military experience nor the strategic ability to justify a system; in our opinion, a chain of accidents overruled both captains at Waterloo; and when destiny, that mysterious defendant, is called in, we judge like the people, that naïve judge”

(Hugo 311)

Another reason why I like this section is because of how it is presented by Hugo. He presents it like a travelogue. He tells us how he got there and what he saw when he arrived. I like the way he describes the field of battle itself. He is there on a calm spring day. If it was any other field, we might walk through it and think nothing of what took place there. We can appreciate its serenity. It is the perfect place for quiet reflection. But this field is different. Its serenity is an illusion. There is an undercurrent of trauma, horror, bravery, and death. We see this when we look closer. It is reflected in the ruins. There is a fifteenth-century wall that leads to a stone doorway. In the stone next to the door is a circular imprint. This wall was struck by a French cannonball. Hugo the traveler peers over the hedges and sees something in the distance that looks like a lion. He is at Hougomont, the site of the battle. It is a former château that is now “nothing more than a farm” (Hugo 303). As Hugo walks around, he observes that he can “still feel the storm of combat in this court” (Hugo 304). There is an orchard in three parts that share an enclosure. It is comprised of a garden, the orchard itself, and a wooded area. The garden sits lower than the orchard and is ringed by balusters. It is here where six soldiers of the First Light Infantry were caught by two Hanoverian companies. The Hanoverians stood along the balusters and looked down at their French enemies and shot them down one by one. It took the French fifteen minutes to die. The only traces of this action in 1861 are the forty-three balusters that remain, all pockmarked with gunshot, and one broken baluster that “stands upright like a broken leg” (Hugo 307). I appreciate Hugo’s choice of similes and adjectives. The wall that is “choked with weeds” (Hugo 307) and the pilasters with their “globes like stone cannonballs” (Hugo 307). We see traces of the battle everywhere.

During the battle itself, the tide turns when the great mass of French cavalry, “two immense steel serpents” (Hugo 327), charge to their doom into an unforeseen sunken road. The “inexorable ravine” was “twelve feet deep between its banks” (Hugo 328). Hugo’s description of the battle is epic in scale and awesome in detail. He describes the cavalry charge thusly:

“These accounts seem to belong to another age. Something like this vision undoubtedly appeared in the old Orphic epics telling of centaurs, those titans with human faces and the bodies of horses, who scaled Olympus at a gallop, horrible, invulnerable, sublime, at once gods and beasts”

(Hugo 328)

Hugo shows us the glory, the tragedy, the bravery, and the hopelessness of all who participated in the battle. There is sharp contrast between the serenity of the farm, where Hugo takes a leisurely afternoon stroll, and the report from the guns and the cannons that live in the earth and in the ruins, that shout into the void at those who dare walk the grounds and listen. Hugo captured this perfectly. Napoleon would fall. France would reform. The old monarchies of Europe would reestablish order. It is at the terrible ravine where the cavalry met its fate, after the battle when the dust settled and the armies were collecting their dead, that Thénardier the thief met Georges Pontmercy, the wounded officer in Napoleon’s army. It is this chance (and fictional) encounter that kicks off the events of the novel. More guns will fire. More cannons will devastate anything and everything foolish enough to stand in its way. There will be time for more glory. And more tragedy. Not only does Hugo give us a philosophical problem for private reflection, but he also gives us a great story to read. The reader is in for a treat.