“Mais que diable allait il faire dans cette galère?

(“But what the hell was he going to do in this mess?”)

Molière (Jean-Baptiste Poquelin)

“Every general and soldier felt his own insignificance, was conscious of being a grain of sand in that sea of men, and at the same time felt his own might, being conscious of himself as part of that great whole.”

Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace, page 301

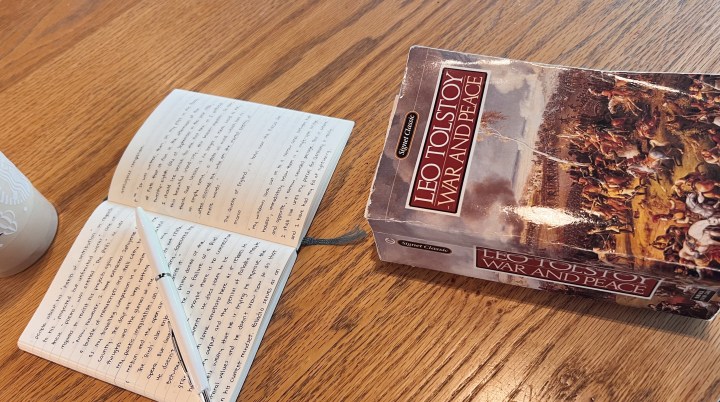

War and Peace is a sprawling epic that is set during the tumultuous reign of Napoleon. The story begins in the summer of 1805 on the eve of the Battle of Austerlitz and concludes with the French invasion of Russia in 1812. The novel brilliantly blends fiction and nonfiction with its portrayal of fictional characters participating in actual historical events alongside actual historical figures. Tolstoy is a master storyteller and has a painter’s attention to detail. His descriptions are rich and complex and poetic but at no time does the narrative feel stifling or overly detailed. Instead, his attention to detail enhances the narrative and allows the reader to completely escape into the story. The reader is immersed in the world he created with his pen. His attention to detail also adds to the believability of the characters he created. They feel like real people that we would interact with in our daily lives.

In addition to creating an amazing story, Tolstoy used the novel as a vessel to criticize the way history was presented at the time. He was especially critical of the prevailing Great Man Theory. He frequently pauses the narrative to interject and challenge this concept in long, detailed, philosophical chapters. Tolstoy believed that history was influenced by the collective contributions of everyone involved. The Great Man Theory said that history was influenced by the actions of “great men”, individuals who are associated with dramatic changes throughout history. It is interesting that Tolstoy chose the Napoleonic period as his subject because many prominent proponents of the Great Man Theory, such as Thomas Carlyle, held Napoleon up as one of the great men of history. It is easy to see why he would choose Napoleon as the effects of the period in which he ruled were still being felt well into the mid-nineteenth century. It isn’t entirely unreasonable to give credit to Napoleon, but Tolstoy’s point was that there were too many other people involved to give him all the credit. He was one of many generals who led their troops into battle. Away from the war, there were many other thousands of people that contributed. Tolstoy emphasized his point by creating many timeless characters and showed that glory was not reserved for a select few but for the many who participated. This book is a celebration of them.

In the spirit of Tolstoy, here is a summary of two characters and their experiences in the Battle of Austerlitz: Prince Andrei Nikolayevich Bolkonsky (“Prince Andrei”) and Count Nikolai Rostov (“Count Rostov”). A brief summary of characters and events is presented at the end of this essay to supplement the reader’s understanding of the historical context. It should be noted that there are minor spoilers below.

The Battle of Austerlitz is one of the major battles of the Napoleonic Wars. We follow the action primarily through the movements of Prince Andrei and Count Rostov. Prince Andrei is attached to the staff of Marshall Kutuzov as an adjutant. Count Rostov is attached to the staff of Prince Bagration as an orderly officer. The battle gets underway, and the narrative stays with Count Rostov. He secretly hopes he will be sent with a message to the Tsar. He gets his wish when Prince Bagration chooses Count Rostov to deliver a message to Marshall Kutuzov about whether to send in his right flank. Marshall Kutuzov is surveying the battle from the Pratzen heights with Tsar Aleksandr. He chooses Rostov knowing that he will most likely be killed.

“Bagration cast his large, sleepy, expressionless eyes over his suite and the boyish face of Rostov, whose heart was throbbing with excitement, was the first to catch his eye. He sent him.”

(Tolstoy 345)

Count Rostov up to this point is still ignorant of the real world. He has a childlike view of how things are supposed to work.

“All his hopes were being realized that morning: there was to be a general engagement and he was taking part in it; not only that, but he was an orderly officer to the most valiant general, on top of which he was being sent with a message to Kutuzov, perhaps even to the Tsar himself. It was a bright morning, he had a good horse under him, and his heart was full of joy and happiness.”

(Tolstoy 345)

Rostov leads us through the battle lines as he carries his orders from Prince Bagration to Marshall Kutuzov.

“Rostov stopped his horse for a moment on a hillock to see what was going on, but however much he strained his attention he could neither make out nor understand what was happening there: men of some sort were moving about in the smoke, lines of troops moved back and forth, but why, who they were, and where they were going it was impossible to discern. These sights and sounds, far from inducing in him any feeling of dejection or misgiving, rather stimulated his energy and determination.”

(Tolstoy 346)

We are with Rostov as he witnesses the “brilliant charge of the Horse Guards” (Tolstoy 347) as they rush into the battle to meet the French cavalry. After some time, Rostov is greeted in turn by his friends who have also participated in the battle. Boris Drubetskoy was in action with the Foot Guards and repulsed an attack. He excitedly runs up to Rostov to tell him of his exploits. Berg, who was “no less excited than Boris” (Tolstoy 348), runs up to Rostov as well to tell him about his experience. He proudly remained at the front, like his ancestors, the knights “von Berg” before him, and he received a bullet wound in his hand for his efforts. Rostov listens to each of their stories but he is confused about what is happening. It’s as if he is in a stupor. His general demeanor is contrasted sharply with his friends’ enthusiasm. His confusion reaches a climax when he looks towards the Pratzen heights and sees French troops instead of Marshall Kutuzov’s suite. This only adds to his confusion. Where is everyone? Rostov keeps moving through the lines looking for Kutuzov or Tsar Aleksandr. He eventually reaches a field where he sees Aleksandr sitting alone on a horse. Rostov is overcome with emotion. Tolstoy gives us some insight into the nature of his character:

“Not one of the countless speeches he had addressed to the Tsar in his imagination recurred to his mind now. Those speeches for the most part had been composed for quite different circumstances, to be spoken in moments of victory and triumph, preferably when he lay on his deathbed, dying of wounds; when, after receiving the Tsar’s thanks for his heroic feats, he expressed to him in words the love he had already proven in deeds.”

(Tolstoy 352)

Instead of moving towards the Tsar, Rostov stays put. He is too afraid to approach him, saying he would rather “die a thousand deaths [than] risk one angry look or his disapproval” (Tolstoy 352). Rostov begins to sadly ride away. Just as he turns his horse, he sees Captain von Toll approach the Tsar. The excitement and nervous energy Rostov felt throughout the battle lifts in an instant. He watches Aleksandr start to weep under the consoling arm of Captain von Toll. Rostov is confronted with the thought that has been silently speaking to him since he began his search for Kutuzov and the Tsar: the battle is lost. All that is left to do is figure out what to do next. Rostov is overcome with emotion at the sight of Aleksandr weeping and weeps in response.

“His despair was the greater for feeling that his own weakness was the cause of his grief”

(Tolstoy 353)

In a desperate fit of courage, Rostov turns to go back but the Tsar is no longer there. Rostov is alone. The fog of battle has lifted and with it, the Tsar, the confidence of the army, and the dreams of a nation.

My interpretation of this scene is that Rostov imagined the Tsar. Rostov was in his first battle and was given a very important task. Or was it? Did Prince Bagration sense the battle was over and therefore decided to send Rostov off on a fool’s errand? Either way, Rostov was given this task that involved him potentially meeting his hero, Tsar Aleksandr. There were so many emotions swirling around in his head he was almost delirious. We see this when he accidentally rides his horse in front of the charging Horse Guards. (Quick aside, the Horse Guards scene didn’t last more than a page but Tolstoy’s description of the charging Guards with their “dazzling white uniforms” (Tolstoy 346) and black horses galloping at full speed towards the waiting French cavalry gave me goosebumps when I read it.) But he was carried through the battle and was protected by his nervous energy. He couldn’t have died on the battlefield. He already knew how he was going to die, or how he was supposed to die. When he sees the Tsar alone in the field, he is confronted with the fact that the battle maybe didn’t go as he assumed it would.

“The sensation of those ominous, whistling sounds, and the sight of the corpses all around him, merged into a single impression of horror and self-pity in Rostov’s mind. He recalled his mother’s last letter. ‘How would she feel if she could see me now,’ he wondered, ‘on this field with cannons aimed at me?’”

(Tolstoy 351)

Up to that point, he was protected still. But that protection was now at an end. Ruined by the reality of war. And who better than the Tsar to break that protection? The Tsar is the man he idolized. A god who should have been standing victorious on the battlefield surrounded by his men was instead left alone in a random field to weep over all that he lost, like a mere mortal. Rostov realizes that events often don’t play out the way we expect them to or even the way they are supposed to. When the battle ends, the men who died for him will have died in vain. Rostov is now left alone like the Tsar trying to make sense of an absurd situation. Tolstoy highlights this absurdity with the Horse Guards. Only eighteen men survived the charge. Tolstoy expertly portrays Rostov as an inexperienced youth by showing him as a clumsy rider. Compared to the noble Horse Guards, it makes him seem like a child playing at war. He foolishly continues through the battle lines carrying his orders from Prince Bagration out of some personal sense of duty. A child’s way of looking at the world. An experienced adult would have recognized the situation for what it was and reacted accordingly. But Rostov wasn’t able to recognize this until the moment he saw the Tsar. Rostov was figuratively riding to the moment where his childhood would end.

“The idea of defeat and flight was inconceivable to Rostov. Though he saw the French cannon and French troops on the Pratzen heights, on the very spot where he had been told to look for the Commander in Chief, he could not, and would not, believe that.”

“The Tsar’s cheeks were sunken, he was pale and hollow-eyed, but the charm and gentleness of his face was all the more striking”

(Tolstoy 352)

The interaction with the Tsar, whether real or not, serves as a good metaphor for the challenges we face in chaotic situations. War serves as a good backdrop for this because even when you feel like you win, you lose. And when you lose, you lose in a major way.

Rostov’s experience is contrasted sharply with Prince Andrei. Whereas Rostov is young and idealistic, Prince Andrei as a world-weary intellectual who tires of the aristocratic life he leads with his wife, Lise. They are expecting a child together and they spend their evenings attending soirees and balls. He has many interactions with his best friend Pierre throughout the story. He has a conversation with him before the battle that gives the reader insight into the nature of his character.

“If everyone fought only for his convictions, there would be no wars,” he said.

“And what a splendid thing that would be!” Pierre responded.

Prince Andrei smiled ironically.

“Very possibly it would be splendid, but it will never be…”

“And why are you going to war?” asked Pierre. “Why? I don’t know. Because I must. And besides, I’m going—” he paused. “I’m going because this life I am leading here—this life is—not to my taste.”

(Tolstoy 53)

He also confides to Pierre that he doesn’t want to be married. Pierre thinks of his friend as having an “easy demeanor” (Tolstoy 57), an “extraordinary memory” (Tolstoy 57), and “erudition (he had read everything, knew everything, had an opinion on everything)” (Tolstoy 57). Prince Andrei had become weary of life and was looking for an escape. His inability to find an outlet for his aspirations is reminiscent of Pechorin in Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time. He has ambition but he doesn’t know how to define it, and even if he could, he wouldn’t know where to apply it.

The narrative focuses on Prince Andrei, who was on the Pratzen heights with Marshall Kutuzov and his suite. Due to a miscalculation by the Russian generals on the location of the main French army, they were threatened almost immediately. Once the French army realized that Kutuzov himself was on the Pratzen heights, they began firing on the battery. The Russian army started retreating and Kutuzov’s suite of generals fled in the panic. Kutuzov asks Prince Andrei what is going on.

“Stop those wretches!” gasped Kutuzov to the regimental commander, pointing to the fleeing soldiers. But at that instant, as if in retribution for these words, a shower of bullets, like a flock of tiny birds, whistled over the regiment and Kutuzov’s suite”

(Tolstoy 342)

Prince Andrei underwent a major character change in an instant. Their position is threatened and Kutuzov pleads with him:

“Bolkonsky,” he whispered, pointing to the routed battalion and at the enemy, “what is this?”

But before he had finished speaking, Prince Andrei, choked by tears of shame and rage, had leaped from his horse and was running to the standard.

“Forward, lads!” he shouted in a childishly shrill voice.

“It has come!” he thought, seizing the staff of the standard, and relishing the whistle of bullets which were evidently aimed at him.

Several soldiers fell.

“Hurrah!” cried Prince Andrei, and scarcely able to hold up the heavy standard, he ran forward, fully confident that the whole battalion would follow him.

And, indeed, he ran only a few steps alone. One soldier followed, then another, till the whole battalion had run forward shouting “Hurrah!” as they overtook him.

(Tolstoy 343)

The change in Prince Andrei is signaled by the description of his shout in a “childishly shrill voice.” Prince Andrei probably hadn’t been this animated since he was a child, and therefore had difficulty finding his voice. Once he found his voice, Prince Andrei picked up the standard and charged forward. The action slows down and we feel every bullet that whizzes by his head. The danger is palpable and ever-present. His internal monologue takes over from the narrative. We follow him as the battery is overrun by the advancing French army. The entire scene is a perfect metaphor for the moment when adrenaline takes over and our experience becomes discorporate. When we are running on adrenaline, we don’t feel the pain because our brain doesn’t want us to feel the pain. We will feel it when it tells us we are ready. As a result, the pain is somewhere out there, in the ether, following us like a specter hovering over our shoulder, waiting to strike us cold. When the adrenaline is flushed out of our system and our normal nervous system takes back over, the pain hits us. It hits Prince Andrei like a bludgeon, both figuratively and literally. When the dust settled, Prince Andrei was laying on the battlefield looking up at the sky.

“’How quiet, solemn, and serene, not at all as it was when I was running,’ thought Prince Andrei, ‘not at all as it was when I was running, shouting, fighting; not like the gunner and the Frenchman with their distraught, infuriated faces, struggling for the rod; how differently do those clouds float over the lofty, infinite heavens. How is it I did not see this sky before? How happy I am to have discovered it at last! Yes! All is vanity, all is delusion, except those infinite heavens. There is nothing but that. And even that does not exist; there is nothing but stillness, peace. Thank God…’”

(Tolstoy 344)

Both Marshall Kutuzov and Prince Andrei were injured in the battle. Kutuzov would be allowed to lead the retreat of the Russian army back to Russia and the wounded Prince Andrei was taken prisoner. Napoleon’s personal doctor reviewed the captured and wounded officers on the field. He says of the wounded Prince Andrei:

“A nervous, bilious type,” said Larrey. “He won’t recover.”

(Tolstoy 360)

The Battle of Austerlitz is the conclusion of Book I and ends on something of a cliffhanger. The reader will have to wait to see how the events of the battle play out. Just as the battle had a major impact on the Napoleonic Wars, it will have a major impact on the characters of Count Rostov and Prince Andrei. Both Prince Andrei and Count Rostov were forced to confront their true selves. And both came out changed men. It is a good metaphor for life. That sometimes we are forced to confront ourselves before we are ready. Circumstances force our hand. All we can do is try to be prepare ourselves as best we can. This essay began with a quote by Molière that Tolstoy gave to Pierre but it served as a good quote to describe the battle and the overall theme of the book. It is fitting we should give Pierre and Molière the last words.

“Who is right and who is wrong? No one. But while you’re alive—live: tomorrow you die, as I might have died an hour ago. And is it worth tormenting oneself when one has only a moment to live in comparison with eternity?”

(Tolstoy 389)

“We die only once, and for such a long time.”

Molière (Jean-Baptiste Poquelin)

The characters in War and Peace are a mixture of real historical figures and fictional characters. The following is an abbreviated list of characters that the reader may find useful. If you are interested in a full list of characters, there is an abundance of reference material available for this book and for the Napoleonic Wars.

Fictional Characters

- Prince Andrei Nikolayevich Bolkonsky – only son of the Bolkonsky family. He is married and expecting a child with his wife, Lise. He is one of the main characters.

- Count Pyotr “Pierre” Kirillovich Bezukhov – an illegitimate child who inherits a fortune. He is the character who is most like the author, Leo Tolstoy. His best friend is Prince Andrei. He is also one of the main characters.

- Count Nikolai Ilyich Rostov – The oldest son of the Rostov family. He is a student at university who gives up his studies to join the war effort. He refuses to use his family contacts to gain a prominent position in the army.

- Lieutenant Alphonse Karlovich Berg – A Russian-German soldier who is engaged to Vera Rostov, who is Nikolai’s older sister and the eldest child in the Rostov family. He participates in the Battle of Austerlitz and has a minor role.

- Prince Boris Drubetskoy – a childhood friend of the Rostov family. Participated in the Battle of Austerlitz and later marries the wealthy Julie Karagina.

- Captain von Toll – a German soldier who participated in the Battle of Austerlitz. Later is a colonel during the invasion of Moscow in 1812.

Historical Events

- Battle of Austerlitz – a pivotal battle in the War of the Third Coalition. Also called the War of the Three Emperors (Francis I of Austria/Holy Roman Emperor Francis II, Aleksandr I of Russia, and Napoleon of France). Napoleon had seized Vienna the month before the battle. The arrival of the Russians provided much needed support to the crumbling Austrian army. The French lured the Allies into battle where they were victorious. Austria immediately capitulated and sued for peace. The Russian army was allowed to retreat into Russia. The battle marked the end of the Holy Roman Empire, which had existed since the reign of Charlemagne in 800. The German client states were organized into the Confederation of the Rhine and pledged to provide troops to Napoleon. The growing French influence in Central Europe would later lead Prussia into war with France in the War of the Fourth Coalition in 1806.

Historical Figures

- Napoleon Bonaparte – Emperor of France and the leader of the French Army. One of the most decorated generals in history. His tactics are still analyzed by military historians. Led France through the various coalition wars and left an indelible mark on the map of Europe. He was ultimately defeated by an army of the seventh coalition led by the Duke of Wellington and Field Marshal von Blücher at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. The European map was changed forever as a result of these wars and the effects are still being felt to this day.

- Prince Pyotr Ivanovich Bagration – general in the Russian army. Along with Marshall Kutuzov, he was a veteran of Alexander Suvorov’s army in the wars of the late 1700s and was a master tactician in rear guard and advance guard actions. He was mortally wounded during the Battle of Borodino prior to the invasion of Moscow. Napoleon was reported to have said of him: “Russia has no good generals. The only exception is Bagration.”

- Prince Mikhail Illarionovich Kutuzov – Marshall of the Russian Empire and one of the most decorated soldiers in Russian history. Led the Russian army at the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805 and again in 1812 when Napoleon was marching on Moscow. During the French invasion of Russia, Kutuzov lured Napoleon’s army into small skirmishes in a series of Pyrrhic victories. Moscow itself was burned but Kutuzov kept his army intact and forced Napoleon into a war of attrition he had no chance of winning. Napoleon was forced to retreat in disgrace in the first major defeat of the French army. Like Prince Bagration, he was a veteran of Alexander Suvorov’s army in the wars of the late 1700s.

- Aleksandr I – the young emperor of the Russian Empire who assumed the throne in 1801 after his father, Paul I, was murdered. Led Russia through the tumultuous Napoleonic Era and represented Russia at the Congress of Vienna that was tasked with putting Europe back together after the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815.