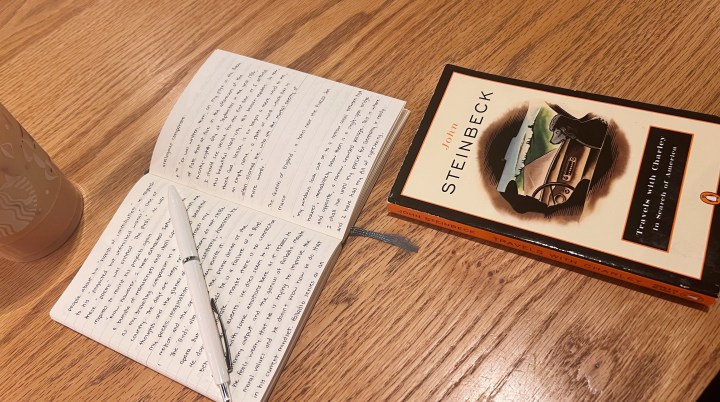

Travels with Charley: In Search of America, is a travelogue written by John Steinbeck. Here are some thoughts about the book.

There were many things I liked about Travels with Charley, John Steinbeck’s account of his cross-country trip around the United States with his trusty French poodle, Charley. I like that the entire trip felt like one seamless journey. He didn’t skip around and report on only the highlights. He recorded when he talked with locals at roadside restaurants; when he talked with random people who were camping in the same location as him; and when he shared food, drink, and conversation with kind strangers he met randomly along his journey. He told you what canned food he was eating for dinner, what his coffee tasted like, and he pointed out the different features of his customized truck, Rocinante, which he named after Don Quixote’s horse. Him and Charley became characters in what could have been a novel he had written years before. He used the word “vacilando” to describe himself on this trip, which is a Spanish word Steinbeck defined on page 63 as:

“he [who] is going somewhere but he doesn’t care if he gets there or not, although he has direction.”

For him, the goal was to see his country one last time, meet the people who inhabited it, and see some beautiful places on the way.

I think one important observation was the general feeling of restlessness that Steinbeck said he encountered everywhere he went. He said on page 10:

“I saw in their eyes something I was to see over and over in every part of the nation – a burning desire to go, to move, to get under way, away from any Here.”

I think this is an interesting observation, not only because it appears relevant even in 2021, but because America at the time was rapidly modernizing. The interstate highway system was brand new. The previous decades had been marked by world wars and crippling depression. It was as if the people had finally found some stability and they were eager to see the world and see what it had to offer. There was a scene where he had dinner with the proprietor of a roadside inn and his son, and his son was anxious to see the world. He subscribed to magazines and wanted to move to New York. He must have reminded Steinbeck of himself at an early age. Steinbeck moved to New York in 1925 after briefly attending Stanford University. I think what he saw in the people he encountered was potential and inspiration. He made his trip in 1960, decades after he had written Grapes of Wrath and Of Mice and Men. He was famous before World War II, and in the war and post-war years, America had changed significantly. It went from being ravaged by the Great Depression to being a world nuclear power and a symbol of postwar posterity. There is a moment where he highlights this, whether consciously or not. He was crossing the Mojave Desert and he talked about crossing the same desert in the 1930s before air conditioning and how the traveler was at the mercy of the elements. On his trip, there were air-conditioned shops along the way. The traveler was not alone.

I also liked that he was honest. When he was sad, he told us he was sad. When he was scared, he told us he was scared. When the weariness of the road caught up to him, we felt it. We were right there with him. And I think very importantly, when he was lost, he admitted it. There is so much wasted energy spent every year by people trying to show how different they are from everyone else. They refuse to show any weakness and vulnerability. As if somehow being human is something to be ashamed of. Life isn’t perfect and we should stop torturing ourselves trying to maintain the illusion that it is.

I think he made the trip as a test for himself to see if he still had something to say about America. He had a lot to say about the American spirit in his novels from the 1930s, but was he able to capture the zeitgeist of a new generation who had grown up during the war and post-war years, with interstates and supermarkets and houses full of appliances and gadgets? I think he was up to the challenge, but I think he was sometimes disillusioned with his task. He says on page 139:

“I came out on this trip to try and learn something of America. Am I learning anything? If I am, I don’t know what it is.”

He is fascinated by the mobile home, something he sees a lot of potential in. He discussed roots with a family who lives in a mobile home. They were ready to move at a moment’s notice. On page 100, the father responds to his question about raising children without roots:

“How many people today have what you are talking about? What roots are there in an apartment twelve floors up? What roots are there in a housing development of hundreds and thousands of small dwellings exactly alike?”

He laments the fact that the interstates have replaced the small country highways and that roadside restaurants offer sterile, tasteless food. He actually made a point to avoid the interstates when he could because he wanted to see the different communities. He says on page 90:

“When we get these thruways across the whole country, as we will and must, it will be possible to drive from New York to California without seeing a single thing.”

He is fully aware that the world is changing. He embraces it and talks about the change, in only a way someone in his unique position can. He has a novelist’s way of looking at the world. He was born in 1902, one year before the airplane was invented. He died in 1968, almost a decade after we started exploring outer space, and one year before man would walk on the moon. He lived through some of the most abrupt changes seen in any period in history. He talks about change when he goes home to California. He observes that his friends and family have all moved on with their lives. They, and him, are no longer the same people. He says on page 206:

“My town had grown and changed and my friend along with it. Now returning, as changed to my friend as my town was to me, I distorted his picture, muddled his memory.”

It was in this section that he formally said goodbye to his hometown. On page 208, he says:

“I printed once more on my eyes, south, west, and north, and then we hurried away from the permanent and changeless past where my mother is always shooting a wildcat and my father is always burning his name with his love.”

He said something that resonated with me, as I had read a similar sentiment in Goethe’s Italian Journey. On page 108, he says:

“I’ll tell you what it was like. Go to the Ufizzi in Florence, the Louvre in Paris, and you are so crushed with the numbers, once the might of greatness, that you go away distressed, with a feeling of constipation. And then when you are alone and remembering, the canvases sort themselves out; some are eliminated by your taste or your limitations, but others stand up clear and clean. Then you can go back and look at one thing untroubled by the shouts of the multitude.”

Traveling is a tiring endeavor. Whether you drive or you fly, you are crossing large parts of the world. Humans weren’t designed for long journeys. We suffer from jet lag, and from aches and pains from sleeping in a camper, and from the fatigue of staying awake all day staring at the lines on the road. We get burned out on living out of a suitcase and eating the same meals every day. To make these journeys, we have to overcome ourselves. We have to overcome our natural inclination to stay safe and comfortable. There are ups and downs with any journey. But years later when you sit back and reflect on all that you have seen, you find that you learned a lot about yourself, and about the world around you. And those teaching moments plant the seed of inspiration for the next journey you will take.

Here are some other quotes that resonated with me:

On winter:

“For how can I know color in perpetual green, and what good is warmth without cold to give it sweetness?” page 36

On coffee:

“I poured him a cup of coffee. It seems to me that coffee smells even better when the frost is in.” page 29

On George, the angry grey cat:

“If the bomb should fall and wipe out every living thing except Miss Brace, George would be happy.” page 51

On the traveler’s interpretation:

“Joe and I flew home to America on the same plane, and on the way he told me about Prague, and his Prague had no relation to the city I had heard and seen. It just wasn’t the same place, and yet each of us was honest, neither one a liar, both pretty good observers by any standard, and we brought home two cities, two truths.” page 77

On the wisdom of our canine friends:

“But Charley doesn’t have our problems. He doesn’t belong to a species clever enough to split the atom but not clever enough to live in peace with itself.” Page 269